Sweating in Shillong: Why temperatures in India’s biodiversity hotspot are rising

Image Credit: Sanjit Das/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Sitting in the glass-and-concrete State Convention Centre in the capital of hilly state, Meghalaya, participants of a media workshop on climate change were feeling sweaty. The convention centre is not air-conditioned nor does it have ceiling fans. For the comfort of guests, some pedestal fans were plugged in.

“Why are we sweating in Shillong?” asked state information technology minister Dr M Ampareen Lyngdoh. The question may sound strange for those who have read in tourist brochures and text books about the wettest places on the planet being in Meghalaya and about its round-the-year cool weather.

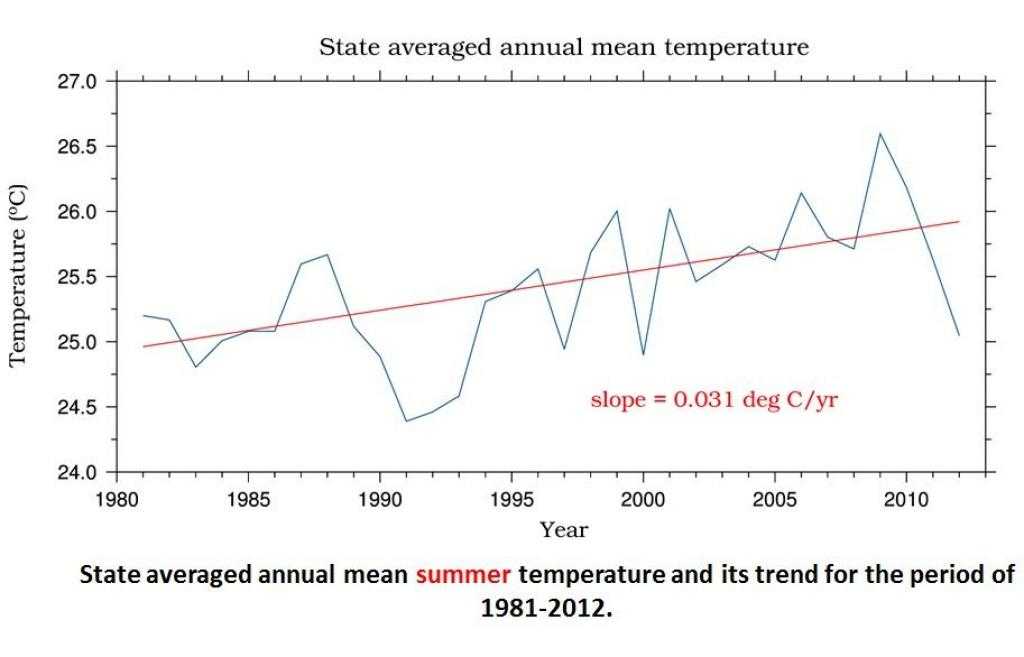

The answer to this question came in the form of a new study done by researchers from the Water and Climate Lab at Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Gandhinagar. The study has shown that air temperature in the state is rising at the rate of 0.031 degree per year. The trend is consistent from 1981 to 2014, barring the years 1991 and 1992. This translates into 1 degree centigrade rise between 1981 and 2014, which is quite significant. Future projections indicate similar rise over next two decades.

The state has also been witnessing highly fluctuating frequencies of hot days, hot nights, cold days and cold nights. “The number of hot days and nights show an increasing trend while that of cold days and cold nights show a declining trend. These are indications of a consistently warming region,” pointed out lead author Dr Vimal Mishra while presenting results of the study commissioned by the state government. “The higher number of hot night frequencies is a matter of concern for the state.”

Based on historic and observed data as well as computer models, the study has projected changes over short-term (2013-2040), mid-term (2041-2070) and long-term (2071-2100) for the state. It is a high-resolution study in the sense that projections have been made for grids of 5X5 km size, so as to help in vulnerability assessment for each grid and adaptation planning at local level.

Future projections show an increasing temperature rise under different scenarios. Under these projections, the rise in maximum temperature in Meghalaya in the long term ranges from 2.65 degree to 3.8 degree, while the rise in minimum temperature will be between 2 degree and 3.5 degree in the long term. The increase in temperature may result in higher number of extreme hot days and nights. Under the extreme scenario projection, the number of hot days could be as high as 100 a year. Similarly, there may be a decrease in extreme cold days and nights.

“The state has already seen a rise of temperature of 1 to 1.5 degree in the past three decades, and the projections point to a similar rise by 2040. If temperature in Meghalaya will rise by about 3 degree rise in a span of half a century, we don’t know what Meghalaya will be like in future – West Bengal or Assam?” wondered Dr Mishra.

There will be changes in the rainfall patterns too in future. The central plateau region is projected to experience an increase in rainfall at a higher rate than the rest of the state. The occurrence of extreme rainfall events will also show an upward trend under various projected scenarios. “The West Khasi hills which already receive very high precipitation are projected to face even higher rise in precipitation,” Dr Mishra added.

The changing climate in Meghalaya, he said, would have widespread implications for forests, water resources, biodiversity, agriculture, livestock and human health. For instance, due to significant rise in temperature, forest fires may go up while extreme rainfall events will increase risk of landslides in high altitude areas causing siltration of water bodies downstream. The rise in temperature will also threaten endemic plant species many of which are already on the verge of extinction. Rainfed agriculture in the state will be adversely hit with crop yields and production declining. Higher temperature will also induce premature breaking of insects and pests.

“Meghalaya has some of the most vulnerable districts to current climate risks and long term climate change in the region,” pointed out Prof NH Ravindranath of Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore. “Sectors like agriculture, forests, fisheries, horticulture are already subjected high climate risks currently and will be highly vulnerable to climate change risks in future. We need to prepare both incremental as well as transformational adaptation plans to make based on vulnerability assessments.”

The workshop was jointly organized by the Department of Science and Technology, Indian Himalayas Climate Adaptation Programme (IHCAP) and Centre for Media Studies.